Over the past decade, investment in laser cutting automation has proliferated, and for good reason: Workers can’t keep up. Machines have become so fast that denesting, not the cutting itself, has become the constraint. This has driven some dramatic developments in blanking automation in recent years, from basic load/unload to advanced storage and retrieval systems, and even automated cells that use automated guided vehicles (AGVs) to connect blanking and bending.

If you haven’t automated your laser cutting operation, where should you start? And if your automation journey’s stalled, how can you get it started again? To answer both questions, The Fabricator spoke with Nick Plourde. The project specialist with Elk Grove Village, Ill.-based MC Machinery Systems—who, incidentally, got his start in this industry as a laser operator—walked through four foundational elements to help point your team in the right direction.

1. Know the Automation Alternatives

To know what’s possible, you first need to know the kinds of blanking automation available. Here, process mapping provides a baseline.

“As a first step, we watch everything and go through existing best practices,” Plourde said. “We focus on process improvement, look at existing layout, including where the material is coming from and where it’s going. We’re looking to optimize flow.”

From there, imagine how your customer mix could evolve, hypothetically, and marry that concept with the myriad automation options on the market.

To illustrate, Plourde described a hypothetical contract fabricator many years into its blanking automation journey. This hypothetical operation has one plant dedicated to a handful of high-quantity customers that demand similar products. Each product family has a highly defined value stream similar to that of an OEM. Here, blank-to-bend automation feeds cut and formed parts to welding, paint, and assembly cells downstream.

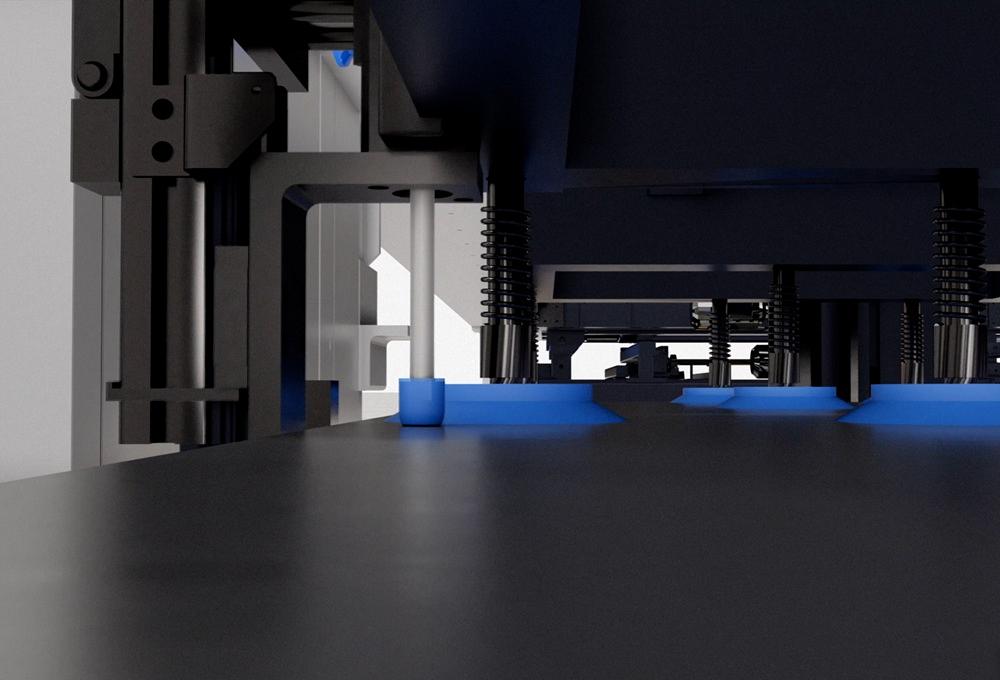

Blank-to-bend automation incorporates material-delivery AGVs that link the two processes (see Figures 1 and 2). This stands apart from arrangements in which AGVs deliver cut material to work-in-process locations in different areas of the plant. The technology, Plourde said, effectively makes cutting and bending a “single process,” with the overall cycle time measured from the first cut to the final bend.

He added that blank-to-bend automation can be highly configured to match a manufacturer’s application requirements. That said, one potential arrangement could start with a laser cutting system with an automated part sorting system that stacks blanks onto a pallet. Those pallets span across two supports that give clearance for an AGV to move underneath. The AGV lifts the pallet, then moves it to a robotic bending cell with a similar AGV docking station. RFID tags communicate with the material handling robot to convey where those stacks of blanks are. From there, the robot grasps the first blank per the program, moves it to a squaring table, then commences the bend sequence.

“The critical element is the software that communicates with all the machines,” Plourde said, explaining that software ensures every element of the automation has the information it needs at a given time. “We need transparency, and we need to record everything. How is the part sorter orienting the parts as it stacks them on the pallet? How many parts are on the pallet that the AGV is bringing over to the press brake? All these factors and more are tracked by software.”

Such a system helps dial in the flow for a defined product family, but what about the “long tail” of medium- and low-quantity jobs within the contract fabricator’s product mix? Here, our hypothetical operation dedicates an entirely different plant, with a blanking department largely divided by material type and job quantity.

In one area, the fabricator has machines with load/unload systems suitable for long runs of specific materials that could occur overnight. Another area might have towers with cartridges that can store raw stock and previously cut nests. This handles a portion of the product mix that requires a variety of different grades and thicknesses. Some setups have a single tower feeding a laser, while others have towers feeding multiple lasers. Other automated machines offer easy access to the work envelope, so specific jobs (like those that use sheet remnants) can be performed manually as needed.

Spanning a wall in a separate area is a large automatic storage and retrieval system that feeds multiple lasers and stores cut blanks for later denesting. This works well for high-quantity products that serve different customers, each requiring a variety of job routings downstream.

2. Factor In Your Nesting, Tabbing, and Denesting Strategy

As Plourde described, all these types of laser cutting automation share a few attributes, including features that help error-proof the process. Suction cup lifters have mechanisms to prevent double-sheet picking, and touch sensors verify sheet thickness (see Figure 3). Some have brushes that sweep over the slats to clear out any slugs and debris from the previous job.

Slats support the sheets during cutting, and how pieces span across those slats affects their stability. A long, narrow part might sit stably across the slats, yet when sitting parallelto those same slats, the piece could tip up and cause a potential head collision—and, hence, require a microtab. The tabs need to be strategically placed so they easily break away without disrupting a downstream operation.

For instance, what if the remains of a tab “rock” against a backgauge finger on a press brake and cause gauging problems? “Here, you might choose a micortabbing method where the tab is left on the skeleton,” Plourde said. The strategy eliminates the need to remove that microtab in a secondary process. The tabbing strategy does leave a tiny divot on the part edge, so it doesn’t work for every part, but it can certainly work to prevent gauging issues at the press brake.

Back in the blanking department, automated laser systems use forks that move in between the slats and underneath a cut sheet. The trick is being able to avoid tabbing where possible while still using tabs where needed to keep the process stable, cycle after cycle, as forks lift cut material from the pallet to an offloading location.

As Plourde explained, modern software and equipment features have helped optimize the process. “Today, software offers optimized toolpaths to ensure a stable cutting process,” he said, defining a “stable nest” as one that makes minimal use of tabs for easy denesting, while remaining secure as the forks move the material to the offloading station.

Having a tab-free nest opens the door for the next level of laser cutting automation: automated part sorting (see Figure 4). Once the laser finishes its cutting cycle, a pallet moves out to an offload station, where part sorting grippers lift and stack pieces. Adapting to different job requirements, certain systems can switch out grippers, moving among suction cups, magnets, specialized lifting tools for hole-intensive parts, and even lifting tools for blank shapes with highly asymmetric centers of mass. After this, forks slide in to lift and remove the skeleton.

Such technology requires kerf widths that allow grippers to remove parts cleanly and reliably. Today, different laser machine manufacturers tackle the kerf width issue in different ways, but whatever the method, the goal is the same: to ensure a smooth, sufficiently wide kerf for easy denesting and stable, automated part removal.

FIGURE 2. As demonstrated at FABTECH 2025, AGVs move along a magnetic track to deliver parts to a robotic press brake.

Certain part geometries might benefit from adding relief areas in the cut program to give grippers the clearance they need to lift the parts without sticking or hangups. When necessary, the programmer might resort to skeleton-destruct sequences, especially for intricate part features that otherwise couldn’t be lifted out reliably.

After cutting and automated part-picking, both the skeleton and remaining slugs (part cutouts) should sit steadily on the slat table so the forks can move in, lift, and remove the scrap without issue (see Figure 5).

3. Empower Personnel With Technology

These days, advanced software and machinery handle much of the minutiae involved in laser cutting, from nesting and toolpath creation to beam centering, as well as optimizing a nest layout for automation. As Plourde explained, major advancements have come even within just the past few years. “Things have changed so much since when I was a laser cutting operator,” he said. “It’s crazy to think about. Technology continues to march ahead.”

When Plourde worked in a shop, he performed tape shots to ensure the nozzle was centered within the nozzle orifice, which he inspected to ensure it was undamaged and free of debris and spatter. Any buildup can alter the flow of assist gas around the laser beam and, hence, drastically change the laser’s cutting characteristics.

He added that modern technology can now help even those with little laser cutting experience to learn what an efficient, reliable laser cutting process looks like. When a shop buys its first system, operators soon gain a sense for what’s needed to keep an automated cutting process productive and reliable. They see how material moves throughout the system, and they work with intuitive software to ensure the automation can run without anyone present. “Before long, they can look at a nest and know what it needs to run unattended,” Plourde said.

4. Foster Productive Conversation

“Technology has progressed significantly,” Plourde said, “but, of course, the real world isn’t perfect.” This, he said, is where the final foundational element—communication—comes into play.

Plourde recalled that during his time working at a fab shop, having operators talking with programmers was baked into shop procedures. As just one example, laser operators arriving on second shift would have quick stand-up meetings with the first-shift operators about the evening’s work. Does everything look stable? Do tabbing strategies account for the effects of distortion and the needs of downstream operations?

Intelligent software and intuitive controls have made laser cutting easier to learn and optimize, especially when it comes to tabbing and toolpath details. Even so, the need for effective communication remains.

Describing how fabricators can start their laser automation journey, Plourde returned to the importance of continuous improvement, including efficient flow of information. “How do programmers and operators communicate, and how are they sending work to the laser? Are operators on the first shift talking to operators on the second shift? Did they ensure everything is in working order? Are there established best practices in tabbing? And how are remnants handled?”

Such communication, he said, lays the groundwork for reliable blanking automation that can grow with a fabricator’s evolving product mix. Talking with others up and down the value stream, operators realize the implications of microtabbing and edge quality, and the value of eliminating secondary processes like deburring. And they realize that laser cutting truly isn’t “complete” until it’s stacked and ready for the next major downstream operation.

FIGURE 3. In this automated setup, touch sensors verify sheet thickness, ensuring the correct material is delivered to the laser cutting table.

Freeing the laser cutting constraint is all about keeping material on the move while making the best use of skilled personnel and not relying on an army of manual laborers to load material and denest parts. Illustrating this concept, Plourde again thought about his time as a laser operator, talking with programmers, schedulers, and other shift operators. His goal was to keep the machine running and material flowing.

“I’d sometimes denest right off the shuttle table, if I could finish before the machine stopped cutting the next job. Other times, I’d use a crane to remove the cut nest. It was all about keeping the machine running.”

He added that the need to keep lasers running hasn’t changed, and it rings especially true for laser operators managing automation. Only now, automation handles the heavy lifting—literally. “Automation today keeps that laser running and your parts flowing,” he said. “With that, you’re set to grow.”

中文

中文 English

English